|

As the society becomes more virtual and digital, the world of forms begins to converge. Since all transactions can now be achieved via the smart phone, those transactions, be they shopping for underwear, booking an apartment, finding a date, buying a stock, reading a book or watching a movie have all become essentially the same procedure: Start typing until an algorithm recognizes what you’re after, make your choice from what’s offered, then tap to purchase. Many people’s jobs have become that way as well. Receive an assignment through a team app, make a few decisions in some software and click to deliver your choices, watch while the money appears in your account. While achieving miracles of efficiency for the commerce model, this is a problematic narrowing of experience. With COVID providing additional pressure toward virtualism, like the soviet machine gunners that prevented the retreat of conscripts in the battles of WWII, virtualism is accelerated under de facto enforcement, and live experience is being waterboarded into acquiescence. Getting paid for anything is in essence virtualizing the experience; conversion of a real life labor to cash is actually a sublimation into the world of ideas, since money is a mutual fiction; an abstract placeholder of value. But now that the “information superhighway” ( How quaint that sounds now) connects all interactions, value seeks its lowest possible level. Along with shopping for the usual goods, services have fallen under the same “click to compare” interrogation, fine for business, but it now applies as well to every aspect of culture. Services like Spotify, Amazon Prime, Getty Images, YouTube, Yelp, and countless others create a race to the bottom of value for artists and businesses alike. I was even browsing some 18th century paintings on Ebay, and I should not have been surprised to see, sprinkled in among the offerings at very low prices, new hand-painted (and very good quality, from what I could tell) replicas of 18th century works, painted in oils in old master techniques- from what must be factory operations in China. Two clicks away. So how then is effort to be valued in a value-dissolving technocracy? The seductive tentacles of virtualization caress the edges of all creative activity, as everything from animation studios, to music production, to design work on Fiverr swoons to the promise of virtual attention- the hope of payment. I’m afraid the result of this mutation is a return to a more feudalized culture, in which the handful of biggest players skim value from the oceans of effort produced lower down in the hierarchy. While an artist or musician (Now a “content provider”) appears on the menu, they can expect pennies from Spotify, Amazon, YouTube or Adobe Stock, etc., because like medieval barons, the companies that own the pipelines amass all the value for themselves, and go to great lengths to shift the property and privileges of ownership from artist to pipeline. After all, the traffic goes to the largest aggregators of content, and they want to keep it that way. Unfortunately, this means that they invariably exercise editorial control to make sure that the content always directs the user back to the pipeline. Economy of scale turns into curation by scale. In this way, the editorial authority of our age has abdicated in favor of the algorithm. Uniqueness has become a liability in the absence of human valuation.

0 Comments

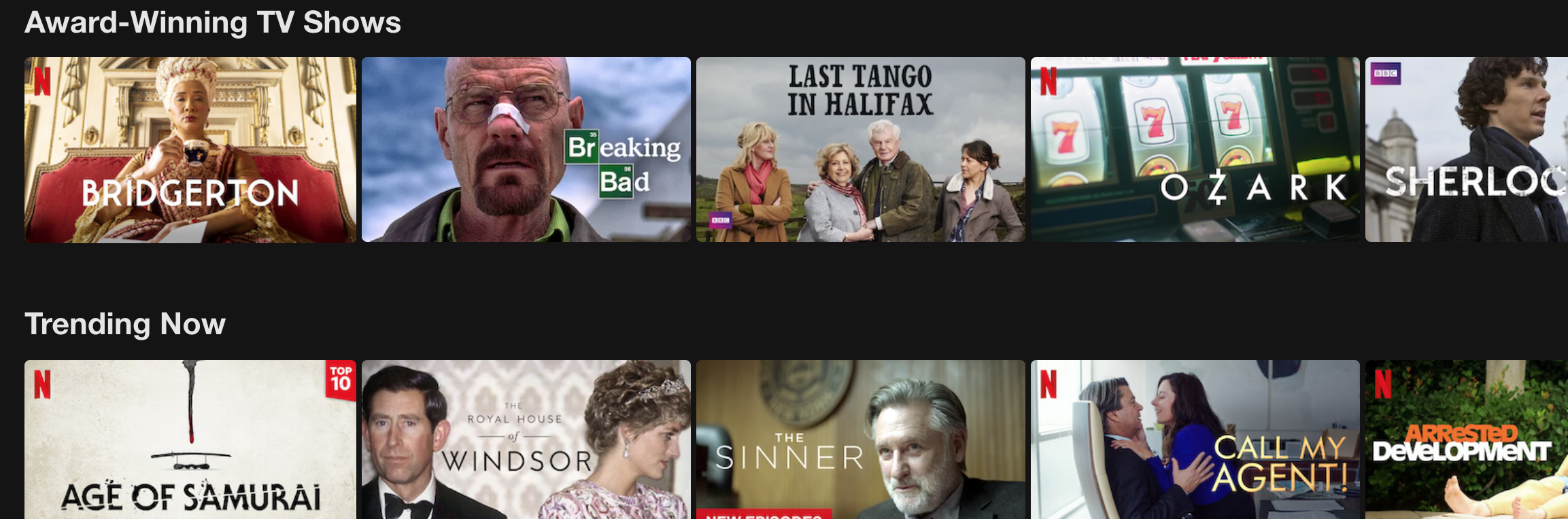

The buzz in the production world around the breakthrough in technique and budget employed by Disney’s The Mandalorian is worth contemplating for those concerned with the future of cinema. The new technique of using a wrap-around LED cyclorama combined with a game engine 3D CG set is a quantum leap into another era of movie production. I remember when I was in film school in the Cretaceous era, and I experimented with the idea of using two TV cameras connected by a motion rig to allow spontaneous camera movement within a green screen set that would exactly match a move on a miniature background. My father the engineer took it upon himself to design and build this rig, but it arrived too late and slightly too imprecise to be used in the production, which was my Columbia puppet thesis project, Banfus and the Search. Instead, I had live sets and theatrical effects which served the purpose well enough for my student thesis needs. But I always had it in the back of my mind that there could be some way of coupling the moves of an active camera with movement in a virtual set. Fast forward to now where everyone’s phone is capable of perfectly tracking dog ears and flopping tongues to your head movements in real time, trailing hearts and stars, without the need of an army of rotoscopers. Exponential increases in computational power have now made it possible to do this essential feat of movie magic on the cheap. Add to this the phenomenon of COVID forcing Zoom interactions on everyone from first-graders to international celebrities in a universal convention of Zoom filters and home green-screen set-ups, and suddenly we are all participating in a massive virtual production experience. A politician appears in a televised Zoom meeting as a lip-synced cat- and he can’t turn it off! Virtual effects not only made cheap, but not even requested! So as remarkable as the technique of the Mandalorian is, it is somehow less spectacular as it merges with the virtual lives we are already living. When Star Wars appeared in 1977, the shock was to see things that could only have been created with laborious feats of miniature sculpture and precision clockwork; the awareness that every frame was labored over infused those frames with meaning and purpose. Now having the ability to simply turn on the “Unreal Engine” (actually the software brand name), we are now allowed the spontaneous rambling around in a virtual world, whether or not it has meaning. The end result is that fantasy can be had on the cheap. Where this takes us, I’m not sure, but I have a hunch that as world creation is becoming ubiquitous, it’s value diminishes, and the public sensitivity for true novelty evaporates as well. The pandora’s box of these techniques is currently knocking about in search of uses. Museums create virtual experience like the Van Gogh exhibit in which spectators walk around in a multi-projected world of what some designers think life would be like inside of an impressionist painting, and makeup counters feature try on makeup on a virtual screen rather than on a customer’s real cheek. I don’t know if we’re really so tired of the IRL world that the accumulation of these endeavors is really an improvement. A better illusion is no more real than a worse one, ultimately it all relies on the suspension of disbelief. -Peter Babakitis  Claire Foy in Netflix's The Crown Claire Foy in Netflix's The Crown I think we are beginning to see some of the effects of monopoly in the very successful new work of the megalithic streaming platforms, namely Netflix, HBO and Amazon. With such offerings as The Crown, The Widow, True Detective, etc., we are now in an aesthetic era somewhere between feature filmmaking and serialized TV. Serialized TV has had a long history in the era of advertising based entertainment through the network era, then the cable era, and now this new milieu of entertainment that earns it’s keep not by pleasing advertisers, or individual cinema ticket buyers, but a new animal entirely; namely the permanent subscription based service that takes as it’s sign of achievement the capturing of an audience that will commit to hours and hours of loyal watching. This brings about a new aesthetic. Not needing to please advertisers kicks it into a the territory of risqué sensationalism to differentiate it from the code of ad based broadcasters, and on the other hand, since the object is long term commitment, easy to understand and traditional cinematic storytelling; templated production style and technique adjusted for the long haul. What seems to be fading is the tolerance for creative, one-off filmmaking, in which risks are taken for that one unique experience that will have no sequel, no loyal repeat audience, but that has the chance to reach the heavens in a moment of singular inspiration. HBO, being the longest player in the subscription game cut its teeth in the era of cinema and from the start was attempting to live up to it’s name, “Home Box Office,” emerging at a time when theatrical cinema was the gold standard, and they wanted to differentiate themselves from the networks, so their aesthetic still has resonance with the earlier form. It was TV in imitation of cinema. While watching The Crown the other night, I was struck by how cinematic and movie-like the production was, but then episode after episode, the very professionalism of the creators begins to dilute itself in the imagination as the same qualities are repeated predictably scene after scene. High marks for professionalism, but diminishing returns for the art of cinema. Which brings us back to the constant threat looming in the background of professionalism vs. art; that thing that the late Anthony Bourdain expressed his disdain for, competence vs. authenticity. As this realm of entertainment becomes saturated with the financially viable, templated big-budget series, perhaps audiences will eventually begin to seek out more unique forms- already YouTube is gathering a larger and larger percentage of online viewing; so that tells me that there is a need for the uncurated. The question will be how a decentralized viewing menu will work logistically for a curious public. Perhaps some technological infrastructure will emerge to connect the curious and eclectic viewer with unique one-off content in a model that can make true cinematic films commercially viable in the new streaming world. -Peter Babakitis |

from eye to eyea different kind of movie Archives

January 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed